Decolonising Digital Public Infrastructure

This post explores whether digital public infrastructure (DPI) can be considered to be a colonial technology and if so, what would be necessary to decolonise DPI?

In recent years the agenda to impose biometric digital-ID across the globe has widened into a ‘digital public infrastructure’ that links biometric digital-ID systems to digital payments systems and data exchange platforms.

This trilogy of technologies enables efficiencies in the state’s digital payments for social security entitlements to citizens such as pensions and benefits, as well as receiving online payments of taxes and fees by citizens and companies.

Originally conceived as a layer of digital public goods under public ownership, the now dominant definition and emerging practice of digital public infrastructure focuses on private-sector partnerships with government digital systems that provide biometric verification of citizen identification and the ability to share citizen’s data across government departments, and between governments and external entities.

Whilst there are benefits to citizens and governments from faster and more convenient identification and payment methods, there are also new risks introduced digital public infrastructure by virtue of holding sensitive biometric and personal data; sharing it with local and foreign, public, and corporate entities; and using it to determine who can access fundamental human rights and entitlements such as social protection, employment, healthcare and education.

Who’s Agenda?

Citizens have not asked for biometric digital-ID or DPI (and in many cases have actively campaigned against it) but powerful interests (often foreign and commercial) are driving the digital public infrastructure agenda. Who specifically?

In recent years the agenda of digital public infrastructure has been promoted by US technology and data companies including Palantir and Mastercard, it has been made effectively compulsory by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), funded by Overseas Development Agencies (ODAs), and supported by development banks, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation for Development (OECD) and private philanthropic agencies like the Gates Foundation.

Yes, but what’s colonial about DPI?

The claim that digital public infrastructure is colonial rests on broader arguments about digital colonialism (sometimes referred to as data colonialism or techno-colonialism). The critique of extractive data practices by foreign technology companies in Kenya was made by African scholars Nanjala Nyabola in her 2018 book Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics, and by Abeba Birhane in her 2020 paper “The Algorithmic Colonisation of Africa. The most extensive articulation of digital colonialism until recently was the 2019 book by Nick Couldry and latin America scholar Uleses Mejia called “The Costs of Connection: which is subtitled “how data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism”. The most recent account is Mirca Madianou’s new (2025) book “Technocolonialism: when Technology for Good is harmful” which includes extended ethnographies of humanitarian agencies imposing the mandatory registering of refugees with digital-ID as a condition for cash transfers and other aid.

Simply put, these authors claim that colonialism and neo-colonialism never went away and that powerful elites in dominant countries have simply developed new mechanisms for extracting value and exploiting those with less power.

They argue that the current phase of digital colonialism is characterised by the algorithmic extraction of data to further the interests of incumbent powerholders. This can be local elites mining public data sets for private or political gain or, on a global level, the USA and China, the IMF and World Bank, Mastercard and Palantir, Google and Amazon, have successfully influenced governments to serve their colonial interests by:

1. restructuring the global economy around data extraction, especially personal data on ever-increasing aspects of human behaviour without meaningful citizen consent, control, or redress;

2. allowing the scraping, leakage and trade of data by commercial aggregators

who use the data to profile citizens and turn life into a commodity for sale to serve the interests of remote corporate and political powerholders while;

3. diminishing citizen agency, human rights, and national sovereignty in a process that imposes colonial ontologies, epistemologies and values, and depends on ever-expanding extraction of data, minerals, electricity and water.

Epistemic Violence

The use of digital technology to commodify ever-increasing aspects of human life reduced to data reminds us of Habermas’ concept of colonising the lifeworld and/or Heidegger’s 1954 thesis “The Question Regarding Technology”.

Heidegger warned that society’s unfettered use of technology requires treating all ecological and human life as a ‘standing reserve’ to be exploited to exhaustion to serve its logics. Having denuded the world’s rainforests and passed peak reserves of fossil fuels, capital is currently restructuring around data.

This necessitates surveillance and extraction of ever-more personal and formerly private aspects of human life for commodification in ways that benefit the world’s richest men in Silicon Valley and Beijing. This process has no logical end, necessitating that all life is reduced to data and that all data sets become interoperable and accessible by state and corporate interests.

What has all this got to do with improving e-Government in Ghana, you ask?

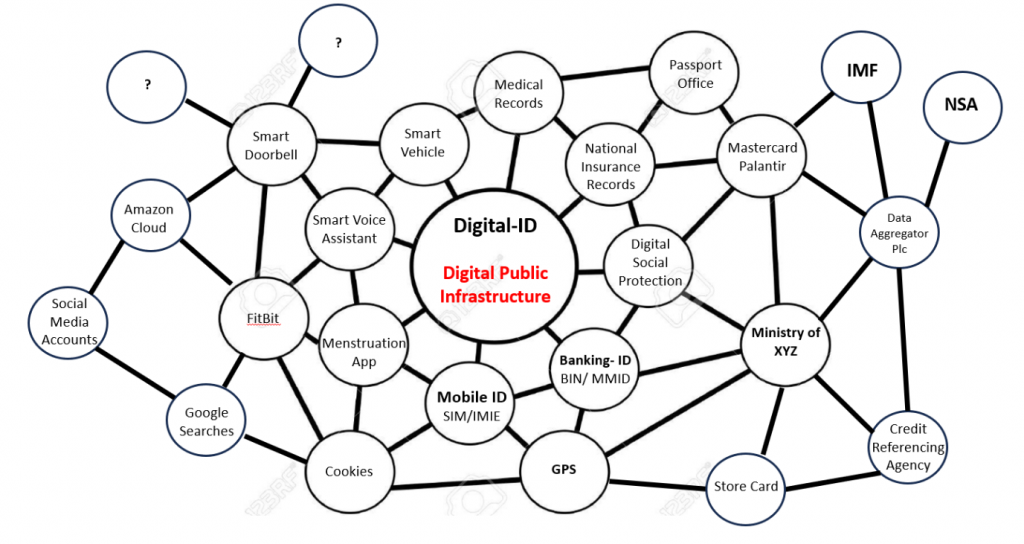

Nobody can reasonably be against the benevolent and efficient payments of social protection to those citizens that are entitled to them. Yet the goals of digital public infrastructure extend far beyond payments to the needy. They aim to integrate all government datasets and to make them accessible across government departments as well as to private companies and foreign entities.

The powerholders marketing DPI always lead with increased convenience to citizens accessing entitlements and services. They are very reluctant to speak about the use of DPI even to facilitate increased tax revenue, let alone sharing data with actors in Washington such as the IMF. The potential for function creep in this regard must be a matter for concern.

Where will it all end?

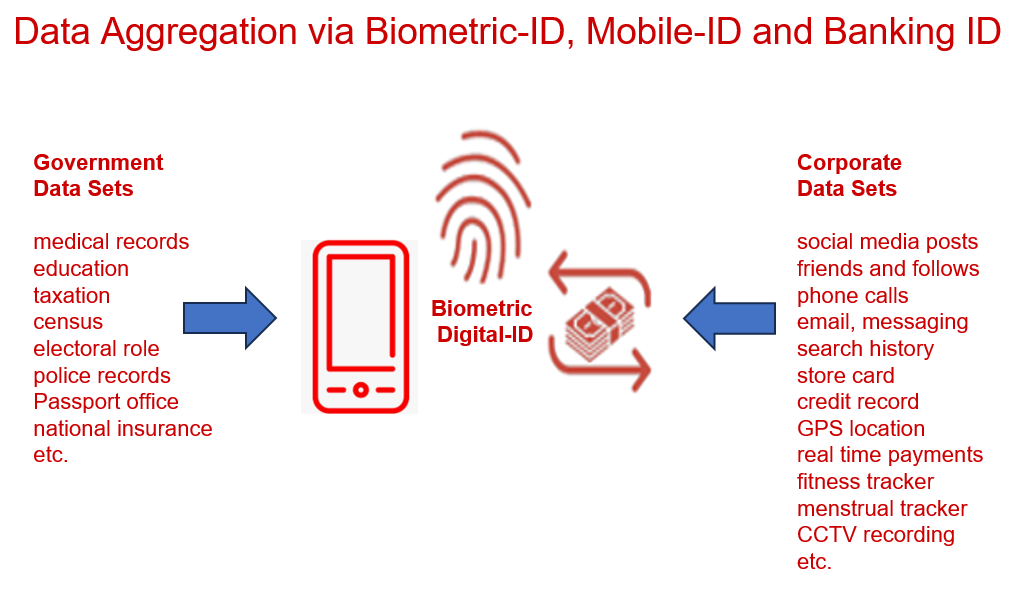

States introduce biometric digital-ID to verifiably link personal identification to the body of each citizen through fingerprints, iris scans or facial recognition. In many countries biometric ID is then made a pre-condition of obtaining a mobile phone SIM-card as well as for accessing mobile money or banking. This provides the state with the potential for a real-time panoptic surveillance of every citizen’s location, purchases, utterances, associations and political preferences.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. Once the state has every citizen’s biometric ID, phone and financial transactions at its disposal, it becomes relatively trivial to add thousands of other data points from other state datasets – such as medical and employment records, driving license, passport etc.

And there is a large and growing sector of commercial data aggregators: companies who pull together corporate data on each citizen including credit referencing data, social media postings, store cards, fitbit records, menstrual calendars, and other data points derived from mobile phone apps and home sensors in the internet of things.

This is why data interoperability is at the heart of DPI.

A Jigsaw not a Conspiracy Theory

That DPI has the potential to expand the existing structure of surveillance capitalism and existing data aggregation jigsaw does not rely on a conspiracy theory or require the identification of bad actors.

It is clear that DPI systems are overwhelmingly built by good people with benevolent intentionssuch as improving the efficiency and convenience of social protection payments and increasing government tax returns.

But these two things can be true at the same time.

An unintended consequence of expanding DPI is extraction of more data. Building ever more sophisticated digital government applications comes with risks. Extracting ever more data from citizen activity, and integrating all government data systems with those of external agencies and corporations remains problematic.

However, in a digital economy where data is the new oil, population-wide datasets with thousands of data points on each citizen are gold mines worth billions. They are the raw material for data aggregators and data analytics companies, either to target advertising or to manipulate political preferences and voting behaviour.

What is Colonial about DPI?

Citizens didn’t ask for biometric digital-ID or DPI or surveillance capitalism. They were not meaningful participants in the design, implementation or on-going evaluation of these systems. So the question arises of who benefits and who’s interests are being served?

It can be argued that digital public infrastructure is colonial if it extracts local data and resources to serve foreign interests.

DPI results in data being extracted from citizens to national governments and from national governments to Washington and other foreign destinations.

It can be argued that digital public infrastructure is colonial if it imposed by global powerholders on remote nations.

DPI is imposed by international funders like the IMF as a pre-condition of accessing credit financing and funding. DPI is subsidised by development banks, ODAs and private philanthropy and is implemented by technology vendors, credit card companies, and international development agencies/think tanks.

It can be argued that digital public infrastructure is colonial if it imposes colonial logics at the expense of local worldviews and ways of knowing.

Couldry and Mejia argue that expanding digital systems impose Western worldviews and extractive logics. DPI relies on reductive instrumental logics that translate the complexity of human life and relationships into binary data. DPI relies upon positivist epistemologies that view the world as knowable from data points and see the purpose of knowledge as enabling prediction, control and manipulation of the world.

It can be argued that digital public infrastructure is colonial if it (re)produces and amplifies existing patterns of inequality and (dis)advantage between countries and along intersectional dimensions including gender, race and class/caste.

Biometric digital-ID has been shown to entrench the exclusion of marginalised groups. DPI systems serve the interests of the USA and China, Palantir and Mastercard and increase the power of state and their ability to surveil citizens.

How to Decolonise DPI

Decolonising this process would require returning autonomy and self-determination to nations and to citizens who have been excluded from the design, implementation and evaluation of digital-ID and DPI systems.

The legitimacy of government – we might argue – lies in the meaningful consent of citizens, and in inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels (as required by Sustainable Development Goal 16.7), as well as the incorporation of mechanisms within DPI for transparency, accountability and redress.

It can be argued that public infrastructure and governance systems should be human-centred not algorithmic and automated, and that they should involve for example disabled and otherwise excluded or marginalised populations in influential roles at all stages of the project cycle.

One route to decolonising DPI would be to reject the view that all human existence is data to be surveilled, and all life is a ‘standing reserve’ of resources for exploitation.

Decolonisation would mean rejecting the Western view that social life is best understood via quantitative analysis of binary data by remote algorithms or that the primary function of knowledge is prediction and control.

Another DPI is Possible.

Citizens can and should be involved in the design, implementation and evaluation of biometric digital-ID and digital public infrastructure more widely – especially those excluded and marginalised by existing systems. Social dialogue about the aspirations and priorities of citizens for improvements in governance should inform the development of digital infrastructure.

Ethical and human rights risk assessments should be carried out before digital public infrastructure is designed or deployed to determine how improving government service delivery can be consistent with existing commitments to data protection, human rights and data sovereignty.

Phrases like “you can’t stand in the way of technology” and “the genie is out of the bottle” are regularly deployed to rob citizens of agency. This form of technological determinism is promoted by the unprecedented PR spend of tech companies and others driving the DPI agenda. Big Tech wants to be unfettered but public interest regulation is necessary to address the potential disadvantage resulting from DPI.

It is also necessary to have well-funded research and investigative journalism, and digital rights organisations with the capacity to track and critique the ideological and material underpinnings of digital colonialism. We must articulate alternative ways of governing digital transformation that give voice to excluded groups and human rights experts at each stage of the design, implementation and evaluation of digital public infrastructure in order to deliver gender, ecological, racial, cognitive justice.